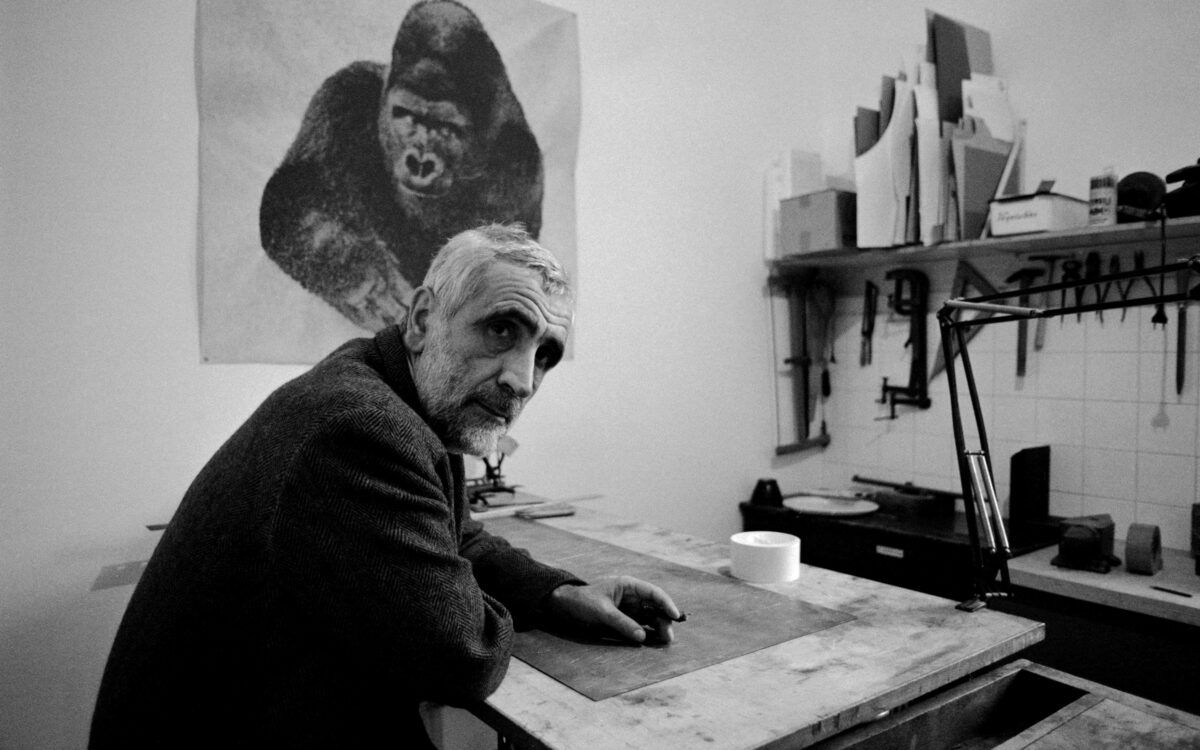

Tribute to one of the greatest Italian masters of design. The beauty lies in the meaning, in the essence of “the only possible form”. Firm in an incessant hard work and in a great consciousness of social and material coherence, Enzo Mari designed archetypes and made them accessible to everyone, again. “Everyone has to design if they don’t want to be designed”.

A designer as well as an artist, critic and theorist, Mari has been an inspiration and reference point for several generations of designers and design entrepreneurs, and his radical ideas have helped shape contemporary design and still have an impact today.

Mari was born in 1932 in Cerano, in the Piedmont region of Italy, and moved to Milan in 1947 taking on a variety of jobs before enrolling at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera in 1952. There, he studied art and literature, with a particular interest in the psychology of vision, the planning of perceptive structures and the methodology of design.

In the late 1950s he met entrepreneur Bruno Danese (who with wife Jacqueline Vodoz launched the eponymous design brand described as ‘long-term project to bring art into everyday life’, changing the face of industrial design), an encounter that helped form Mari’s career as a designer.

With Danese, Mari created one of his best known and loved pieces, the 16 Animali wooden puzzle. From a single piece of oak wood, Mari designed 16 animals through one continuous cut, an object that was inspired by his research into Scandinavian children’s toys, and his own children. Each animal is designed as an object of its own, also fitting neatly within a minimalist puzzle structure: an exercise in formal creativity.

During his 60-year career, Mari went on to conceive over 1500 designs for companies such as Danese, Driade, Artemide, Zanotta and Magis, as well as illustrations, books with Einaudi and Bollati Boringhieri and imaginative works for children now edited by Italian publisher Corraini.

Some of his best known objects include the Putrella tray for Danese, intuitively created from a bent industrial I-bar, an archetypal shape in which Mari recognised an expressive potential. Another iconic piece he designed for Danese in 1966 is the Timor perpetual calendar, a graphic tool that represents his practical approach to creation. Made of plastic cards fixed to a central pivot, the design was inspired by railway signs and long-lasting functionality. Swiss architect Max Bill said that Mari thought creatively and built logically, a fitting description of the duality of his oeuvre.

Although Mari was perhaps more intuitively known for his designs, it is his ideas which make him one of the most radical, revolutionary thinkers of his generation. Mari’s own political views veered towards communism, something that he made sure to be reflected in his work. He saw design as a democratic utopia, a designer’s responsibility towards its community. He claimed that his work was aimed at creating a better world, by looking at future scenarios that he would tackle with his projects.

His political ideas were reflected in his definition of ‘good design’, which he described as sustainable, accessible, functional, well made, emotionally resonant, enduring, socially beneficial, beautiful, economic and affordable.

A project which is perhaps Mari’s most referenced idea and a fitting demonstration of his thinking is the “Proposta per un’Autoprogettazione” (proposal for a self-design) series. A 1974 book presented as an instruction manual to create furniture simply using rough boards and nails, Autoprogettazione represented an economical way to produce furniture while sharing knowledge and creating awareness of the act of making.

Mari closed his studio in 2014, but his impact has always been tangible within the design industry and among creatives from all fields. His creative power is revealed in a recent exhibition at Milan’s Triennale museum (currently on view), curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist with Francesca Giacomelli, make it clear that Mari’s contributions to the creative industries have been far-reaching, and that his legacy will live on.